“Could a common cold virus help fight COVID-19? - Medical News Today” plus 1 more

“Could a common cold virus help fight COVID-19? - Medical News Today” plus 1 more |

| Could a common cold virus help fight COVID-19? - Medical News Today Posted: 29 Mar 2021 07:06 AM PDT

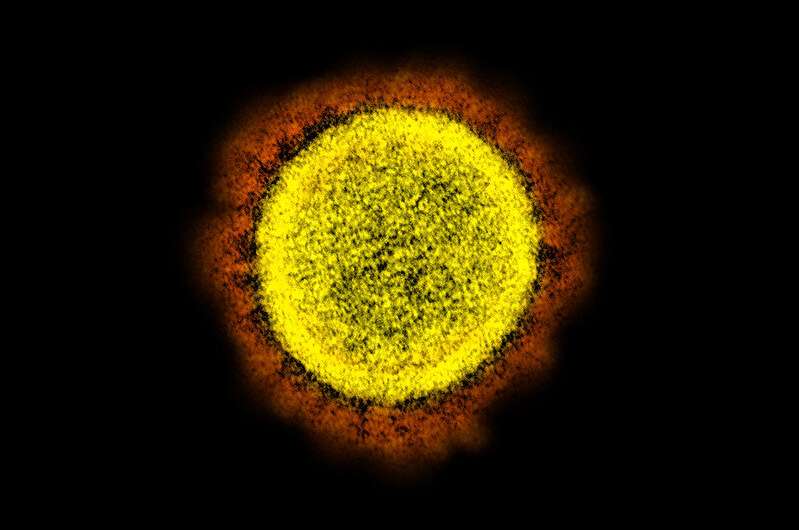

For decades, scientists have been hunting for a cure for the common cold, with little success. However, recent research hints that this bothersome — though usually mild — infection may be a hidden ally in the fight against pandemic viruses such as influenza and SARS-CoV-2. Human rhinoviruses (HRVs), which cause more than half of all common colds, are the most widespread respiratory viruses in humans.

Previous research suggests that HRVs may have inhibited the spread of the influenza A virus subtype H1N1 across Europe during the 2009 flu pandemic. Experts believe that the HRVs did this by inducing human cells to produce interferon, which is part of the body's innate immune defenses against viral infection. Research has shown that SARS-CoV-2 is susceptible to the effects of interferon. This finding led scientists at the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research in the United Kingdom to speculate whether HRVs could help combat the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and limit the severity of infections. To find out, the researchers infected cultures of human respiratory cells in the lab with either SARS-CoV-2, an HRV, or both viruses at the same time. The cultures closely mimicked the outer layer of cells, called the epithelium, that lines the airways of the lungs. SARS-CoV-2 steadily multiplied in the cells that the team had infected with this virus alone. However, in cells also infected with HRV, the number of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles declined rapidly until they were undetectable just 48 hours after the initial infection. In further experiments, the scientists found that HRV suppressed the replication of SARS-CoV-2, regardless of which virus infected the cells first. Conversely, SARS-CoV-2 had no effect on the growth of HRV. To test their hunch that HRV was inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 by triggering the cells' innate immune response, the researchers repeated their experiments in the presence of a molecule that blocks the effects of interferon. Sure enough, the molecule restored the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to replicate in cells infected with HRV. "Our research shows that human rhinovirus triggers an innate immune response in human respiratory epithelial cells, which blocks the replication of the COVID-19 virus, SARS-CoV-2," says senior author Prof. Pablo Murcia. "This means that the immune response caused by mild, common cold virus infections could provide some level of transient protection against SARS-CoV-2, potentially blocking transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and reducing the severity of COVID-19," Prof. Murcia adds. The researchers used a mathematical simulation to predict how different numbers of HRV infections of varying lengths might affect the spread of SARS-CoV-2 through a population. The results showed that the number of new SARS-CoV-2 infections in a population is inversely proportional to the number of HRV infections. The model predicts that if the common cold virus were to become sufficiently widespread and persistent, it could temporarily prevent SARS-CoV-2 from spreading. "The next stage will be to study what is happening at the molecular level during these virus-virus interactions to understand more about their impact on disease transmission," says Prof. Murcia. "We can then use this knowledge to our advantage, hopefully developing strategies and control measures for COVID-19 infections," he adds. The research appears in The Journal of Infectious Diseases. In their paper, the researchers speculate that mild HRV infections might be mutually beneficial for the virus and its human hosts. They write that the immune system may have evolved to allow HRV to replicate and transmit to new hosts. In return, the virus keeps more severe and potentially lethal viral infections at bay. At the Science Media Centre in London in the United Kingdom, other scientists welcomed the research but flagged some potential limitations. Gary McLean, who is a professor in molecular immunology at London Metropolitan University in the U.K., said that the major limitation was that the study involved just one of the 160 or more possible strains of rhinovirus. He said there was no guarantee that each strain would have the same effect on SARS-CoV-2 infections. He added that translating results from a lab experiment to real life is "very tricky," saying:

In addition, he pointed out that intensive infection control measures over the past year have made the common cold less prevalent, reducing the potential for HRV-triggered innate immunity to combat the spread of SARS-CoV-2. For live updates on the latest developments regarding the novel coronavirus and COVID-19, click here. |

| COVID origins report: the four theories in play - Medical Xpress Posted: 29 Mar 2021 08:30 AM PDT  The COVID-19 pandemic origins report looked into four hypotheses as to how the virus entered the human species, ranking them from the most to the least likely. The final report, a joint WHO-China study, which AFP obtained Monday ahead of its official release, spelled out how the joint team of Chinese scientists and international experts thrashed out the hierarchy of probability. Here are the four theories, in descending order of probability: Intermediate host animal This hypothesis, deemed by the experts as a "likely to very likely pathway", argues that the virus first spread from the original host animal, likely a bat, to another intermediate host animal before being passed on to humans. — Arguments for: Although the closest-related viruses were found in bats, the evolutionary distance between those bat viruses and the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 disease is estimated to be several decades, suggesting a "missing link" in between, the report said. Highly similar viruses have also been found in pangolins, suggesting cross-species transmission from bats at least once. The report also pointed out that an intermediary step involving an amplifying host has been observed for several other viruses. — Arguments against: While SARS-CoV-2 has been found in a growing number of animal species, studies suggest they were infected by humans. And so far, tests of a wide range of domestic and wild animals in the region where the outbreak first started have shown no evidence of SARS-CoV-2. — Next steps: The experts suggested the virus might have been introduced through imports to Wuhan of meat from wildlife farms in provinces where bats have been shown to carry similar coronaviruses. "While this does not prove a link, it does provide a meaningful next step for surveys," the report said. Direct transmission This hypothesis, deemed "possible to likely", assumes that SARS-CoV-2 jumped directly from the original host, likely a bat, to humans. — Arguments for: Most current human coronaviruses come from animals, the report said. Surveys, it said, had found viruses with high genetic similarity to SARS-CoV-2 in Rhinolophus bats. It also pointed out that "antibodies to bat coronavirus proteins have been found in humans with close contact to bats". Similar viruses have been found in Malayan pangolin, and mink have proven also highly susceptible, it said, adding it could not rule out that minks might be the primary source. — Arguments against: Though the closest genetic relation to SARS-CoV-2 is a bat virus, analysis indicates "decades of evolutionary space" between them, suggesting an intermediate host route is more likely. "Also, contacts between humans and bats or pangolins are not likely to be as common as contact between humans and livestock or farmed wildlife." — Next steps: Trace-back studies of the Wuhan markets' supply chains provided some "credible leads", which should be expanded to other countries, said the report. Cold food chain This hypothesis, which was deemed "possible", suggests that frozen food products or their packaging might have been a route of introduction and transmission of SARS-CoV-2. — Arguments for: China witnessed some outbreaks related to imported frozen products in 2020. SARS-CoV-2 has been found on the outer package of imported frozen products, suggesting the virus can persist on contaminated frozen products. — Arguments against: "There is no conclusive evidence for foodborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and the probability of a cold-chain contamination with the virus from a reservoir is very low," the report said. — Next steps: The experts called for screening of leftover frozen cold-chain products, especially farmed wild animals, sold in Wuhan's Huanan market from December 2019, if still available. Laboratory leak This hypothesis, which was found to be "extremely unlikely", considers that SARS-CoV-2 was introduced through a laboratory incident. The experts examined only the theory that the natural virus escaped a lab through the accidental infection of staff. It did not consider the hypothesis of deliberate release or deliberate bioengineering of the virus, which scientists have already ruled out. — Arguments for: "Although rare, laboratory accidents do happen", the report said. And CoV RaTG13, the closest strain to SARS-CoV-2, found in bat anal swabs, had been sequenced at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. — Arguments against: "There is no record of viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2 in any laboratory before December 2019, or genomes that in combination could provide a SARS-CoV-2 genome," the report said. "The risk of accidental culturing SARS-CoV-2 in the laboratory is extremely low," it added. — Next steps: "Regular administrative and internal review of high-level biosafety laboratories worldwide. Follow-up of new evidence supplied around possible laboratory leaks." Explore further © 2021 AFP Citation: COVID origins report: the four theories in play (2021, March 29) retrieved 29 March 2021 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2021-03-covid-theories.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "sars,sars cause,sars disease" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment