“Anosmia and changes in brain MRI in COVID-19 - News-Medical.Net” plus 2 more

“Anosmia and changes in brain MRI in COVID-19 - News-Medical.Net” plus 2 more |

- Anosmia and changes in brain MRI in COVID-19 - News-Medical.Net

- Comparative pathogenesis of COVID-19, MERS, and SARS in a nonhuman primate model - Science Magazine

- No specific COVID-19-linked lesions found despite extensive organ injury - News-Medical.Net

| Anosmia and changes in brain MRI in COVID-19 - News-Medical.Net Posted: 31 May 2020 07:59 PM PDT Even as the COVID-19 pandemic was sweeping across the world, new symptoms and clinical presentations appeared, often confusing the picture. A case report from Italy, published in the journal JAMA Neurology in May 2020, shows that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) may be a neurotropic virus, and may cause infection to present primarily with anosmia.  Human Coronavirus InfectionHuman coronaviruses have already been shown to infect the nervous system in small animals. Autopsies of humans who suffered from SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) in 2002 to 2003 showed the presence of the SARS-CoV virus in the brain. Similarly, the SARS-CoV-2 may invade nervous tissue, and this may, partly at least, result in respiratory failure. Coronaviruses (CoVs) are members of the largest group of viruses that are responsible for respiratory and gastrointestinal infections. Members of this group have caused three pandemics in the last two decades: first, the SARS outbreak in 2002, and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) pandemic in 2012. The current COVID-19 pandemic is thus the third outbreak caused by a coronavirus. COVID-19 SymptomsThe symptoms of COVID-19 infection include fever, a dry cough, tiredness, anosmia, loss of taste, a sore throat, gut symptoms like diarrhea, headache, and leg pain. However, the majority of patients with COVID-19 do not know it, being completely asymptomatic, or develop only a mild bout of symptoms like sneezing or coughing. In about 20% of cases, the infection progresses to cause severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure, and sometimes death, in a significant minority of cases. Despite the severe impact on the lungs, more evidence is coming in that the virus can also affect other organs and body systems, which could imply that the pandemic could leave behind acute and chronic sequelae. The Brain and COVID-19This could include neurological conditions. Patients with a history of stroke are among those at higher risk for COVID-19-induced ARDS, as has been shown by numerous case series. Conversely, over a third of COVID-19 patients in a Chinese study, had neurological signs such as acute stroke or loss of consciousness. This is supported by the presence of agitation, confusion, signs of motor neuron involvement, and brain disorder in the majority of patients with this infection in a French study. In fact, the MERS-CoV outbreak was also associated with severe manifestations related to the nervous system. The Case ReportThe case study describes a female radiographer aged 25 years, with no underlying medical illness, who was working in a COVID-19 ward. She had a mild dry cough, which vanished after a day, to subsequently develop persistent and almost complete loss of smell and a weakened sense of taste. There was no fever, then or ever. She had no history of any trauma, seizure, or hypoglycemic episode at any time. On the third day of anosmia, she underwent a fibroscopic evaluation of the nasal cavity, which failed to show any positive findings. A chest CT and CT of the maxillofacial cavities also did not show any particular findings. An MRI of the brain was also carried out, which included both 3D and 2D fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images. The Imaging FindingsThese images showed a hyperintense area in the cortex of the right gyrus rectus, as well as a less obvious hyperintense region in the olfactory bulbs. The occurrence of anosmia in many patients with COVID-19, in Italy, and because the altered cortical image suggested a viral infection of the area, the patient had a swab taken for reverse transcription-polymerase chain (RT-PCR) testing, to detect SARS-CoV-2. The test was positive. A follow-up MRI which was taken after 28 days showed complete resolution of the hyperintensity in the right gyrus rectus cortex, while the olfactory bulbs had become less hyperintense and appeared slimmer. The patient's anosmia eventually resolved. Interestingly, two other COVID-19 patients who also had anosmia did not show any signal alterations in MRIs of the brain at 12 and 25 days from the earliest symptom. The Importance of This Case ReportThe investigators say this is the first time that the human brain has been shown to be involved in a living patient with COVID-19, in the form of an alteration in the brain cortical signal that suggests viral invasion of the brain in a part that is linked to olfaction. The differential diagnoses in this patient could have been conditions like status epilepticus, changes like those seen in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, other viral infections, and anti NMDA encephalitis, but none of these were probable in the clinical circumstances. The subtle changes in the olfactory bulb, in addition to the other MRI findings, led the scientists to wonder if the virus could be invading the olfactory bulb and through this pathway, the brain, causing sensorineural dysfunction of the olfactory sense. However, this can be proved only if the evidence is compiled by the study of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and pathologic studies of the brain tissue. A possible issue raised here is the absence of brain changes on MRI in two other COVID-19 patients who also had anosmia, as well as the disappearance of the MRI changes at the 28-day follow-up examination of this patient. This could indicate the extreme transience of these findings, which might occur only at the earliest stage of infection, or that they do not occur in all patients. Another important finding from this case study is that some COVID-19 patients present only with anosmia, and it is necessary to evaluate this finding in the current situation to avoid missing the diagnosis in these otherwise asymptomatic patients and thus facilitating continued disease transmission from such individuals. Journal reference:

|

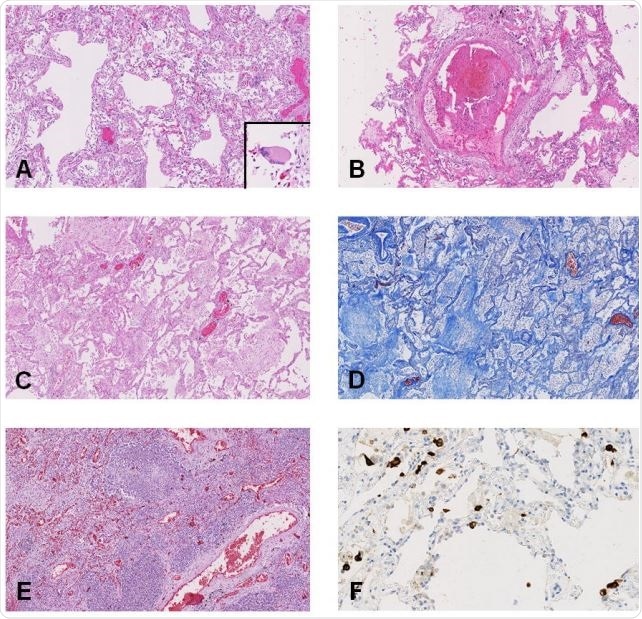

| Comparative pathogenesis of COVID-19, MERS, and SARS in a nonhuman primate model - Science Magazine Posted: 28 May 2020 10:48 AM PDT Coronavirus in nonhuman primatesWe urgently need vaccines and drug treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Even under these extreme circumstances, we must have animal models for rigorous testing of new strategies. Rockx et al. have undertaken a comparative study of three human coronaviruses in cynomolgus macaques: severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus (SARS-CoV) (2002), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)–CoV (2012), and SARS-CoV-2 (2019), which causes COVID-19 (see the Perspective by Lakdawala and Menachery). The most recent coronavirus has a distinct tropism for the nasal mucosa but is also found in the intestinal tract. Although none of the older macaques showed the severe symptoms that humans do, the lung pathology observed was similar. Like humans, the animals shed virus for prolonged periods from their upper respiratory tracts, and like influenza but unlike the 2002 SARS-CoV, this shedding peaked early in infection. It is this cryptic virus shedding that makes case detection difficult and can jeopardize the effectiveness of isolation. AbstractThe current pandemic coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was recently identified in patients with an acute respiratory syndrome, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). To compare its pathogenesis with that of previously emerging coronaviruses, we inoculated cynomolgus macaques with SARS-CoV-2 or Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)–CoV and compared the pathology and virology with historical reports of SARS-CoV infections. In SARS-CoV-2–infected macaques, virus was excreted from nose and throat in the absence of clinical signs and detected in type I and II pneumocytes in foci of diffuse alveolar damage and in ciliated epithelial cells of nasal, bronchial, and bronchiolar mucosae. In SARS-CoV infection, lung lesions were typically more severe, whereas they were milder in MERS-CoV infection, where virus was detected mainly in type II pneumocytes. These data show that SARS-CoV-2 causes COVID-19–like disease in macaques and provides a new model to test preventive and therapeutic strategies. After the first reports of an outbreak of an acute respiratory syndrome in China in December 2019, a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was identified (1, 2). As of 14 March 2020, over 140,000 cases were reported worldwide with more than 5400 deaths, surpassing the combined number of cases and deaths of two previously emerging coronaviruses, SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)–CoV (3). The disease caused by this virus, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is characterized by a range of symptoms, including fever, cough, dyspnoea, and myalgia in most cases (2). In severe cases, bilateral lung involvement with ground-glass opacity is the most common chest computed tomography (CT) finding (4). Similarly to the 2002–2003 outbreak of SARS, the severity of COVID-19 disease is associated with increased age and/or a comorbidity, although severe disease is not limited to these risk groups (5). However, despite the large number of cases and deaths, limited information is available on the pathogenesis of this virus infection. Two reports on the histological examination of the lungs of three patients showed bilateral diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), pulmonary edema, and hyaline membrane formation, indicative of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), as well as characteristic syncytial cells in the alveolar lumen (6, 7), similar to findings during the 2002–2003 outbreak of SARS-CoV (8). The pathogenesis of SARS-CoV infection was previously studied in a nonhuman primate model (cynomolgus macaques) where aged animals were more likely to develop disease (9–13). In the current study, SARS-CoV-2 infection was characterized in the same animal model and compared with infection with MERS-CoV and historical data on SARS-CoV (9, 10, 12). First, two groups of four cynomolgus macaques [both young adult (young), 4 to 5 years of age; and old adult (aged), 15 to 20 years of age] were inoculated by a combined intratracheal (IT) and intranasal (IN) route with a SARS-CoV-2 strain from a German traveler returning from China. No overt clinical signs were observed in any of the infected animals, except for a serous nasal discharge in one aged animal on day 14 post inoculation (p.i.). No significant weight loss was observed in any of the animals during the study. By day 14 p.i., all remaining animals seroconverted as revealed by the presence of SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies against the virus S1 domain and nucleocapsid proteins in their sera (fig. S1). As a measure of virus shedding, nasal, throat, and rectal swabs were assayed for virus by reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and virus culture. In nasal swabs, SARS-CoV-2 RNA peaked by day 2 p.i. in young animals and by day 4 p.i. in aged animals and was detected up to at least day 8 p.i. in two out of four animals and up to day 21 p.i. in one out of four animals (Fig. 1A). Overall, higher levels of SARS-CoV-2 RNA were detected in nasal swabs of aged animals compared with young animals. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in throat swabs peaked at day 1 p.i. in young and day 4 p.i. in aged animals and decreased more rapidly over time by comparison with the nasal swabs but could still be detected intermittently up to day 10 p.i. (Fig. 1B). Low levels of infectious virus were cultured from throat and nasal swabs up to day 2 and 4, respectively (table S1). In support of virus shedding by these animals, environmental sampling was performed to determine potential contamination of surfaces. Environmental sampling indicated the presence of low levels of SARS-CoV-2 RNA on surfaces through both direct contact (hands) and indirect contamination within the isolator (table S2). SARS-CoV-2 RNA was only detected in a rectal swab from one animal on day 14 p.i., and no viral RNA was detected in whole blood at any time point throughout the study. Viral RNA was detected in nasal (A) and throat (B) swabs and in tissues (C) of SARS-CoV-2–infected animals by RT-qPCR. Samples from four animals (days 1 to 4) or two animals (days >4) per group were tested. The error bars represent the SEM. Virus was detected in tissues from two young and two aged animals on day 4 by RT-qPCR. Asterisk (*) indicates that infectious virus was isolated. On autopsy of four macaques on day 4 p.i., two had foci of pulmonary consolidation in the lungs (Fig. 2A). One animal (aged: 17 years) showed consolidation in the right middle lobe, representing less than 5% of the lung tissue. A second animal (young: 5 years) had two foci in the left lower lobe, representing about 10% of the lung tissue (Fig. 2A). The consolidated lung tissue was well circumscribed, red-purple, level, and less buoyant than normal. The other organs in these two macaques, as well as the respiratory tract and other organs of the other two animals, were normal. (A) Two foci of pulmonary consolidation in the left lower lung lobe (arrowheads). (B) Area of pneumonia [staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E); bar, 0.5 cm). (C) Edema fluid in alveolar lumina (H&E; bar, 25 μm). (D) Neutrophils, as well as erythrocytes, fibrin, and cell debris, in an alveolar lumen flooded by edema fluid (H&E; bar, 10 μm). (E) Mononuclear cells, either type II pneumocytes or alveolar macrophages, in an alveolar lumen flooded by edema fluid (H&E; bar, 10 μm). (F) Syncytium in an alveolar lumen (H&E; 100× objective). Inset: Syncytium expresses keratin, indicating epithelial cell origin [immunohistochemistry (IHC) for pankeratin AE1/AE3; bar, 10 μm]. (G) SARS-CoV-2 antigen expression is colocalized with areas of diffuse alveolar damage (IHC for SARS-CoV-nucleocapsid; bar, 50 μm). (H) Type I (flat) and type II (cuboidal) pneumocytes in affected lung tissue express SARS-CoV-2 antigen (IHC for SARS-CoV-nucleocapsid; bar, 25 μm). (I) Ciliated columnar epithelial cells of respiratory mucosa in nasal cavity express SARS-CoV-2 antigen (IHC for SARS-CoV-nucleocapsid; bar, 25 μm). Virus replication was assessed by RT-qPCR on day 4 p.i. in tissues from the respiratory, digestive, urinary, and cardiovascular tracts and from endocrine and central nervous systems, as well as from various lymphoid tissues. Virus replication was primarily restricted to the respiratory tract (nasal cavity, trachea, bronchi, and lung lobes) with highest levels of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in lungs (Fig. 1C). In three out of four animals, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was also detected in ileum and tracheo-bronchial lymph nodes (Fig. 1C). The main histological lesion in the consolidated pulmonary tissues of both the young and aged animals involved the alveoli and bronchioles and consisted of areas with acute or more advanced DAD (Fig. 2B). In these areas, the lumina of alveoli and bronchioles were variably filled with protein-rich edema fluid, fibrin, and cellular debris; alveolar macrophages; and fewer neutrophils and lymphocytes (Fig. 2, C to E). There was epithelial necrosis with extensive loss of epithelium from alveolar and bronchiolar walls. Hyaline membranes were present in a few damaged alveoli. In areas with more advanced lesions, the alveolar walls were moderately thickened and lined by cuboidal epithelial cells (type II pneumocyte hyperplasia), and the alveolar lumina were empty. Alveolar and bronchiolar walls were thickened by edema fluid, mononuclear cells, and neutrophils. There were aggregates of lymphocytes around small pulmonary vessels. Moderate numbers of lymphocytes and macrophages were present in the lamina propria and submucosa of the bronchial walls, and a few neutrophils were detected in the bronchial epithelium. Regeneration of epithelium was seen in some bronchioles, visible as an irregular layer of squamous to high cuboidal epithelial cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. There were occasional multinucleated giant cells (syncytia) free in the lumina of bronchioles and alveoli (Fig. 2F) and, based on positive pan-keratin staining and negative CD68 staining, these appeared to originate from epithelial cells (Fig. 2F, inset). SARS-CoV-2 antigen expression was detected in moderate numbers of type I pneumocytes and a few type II pneumocytes within foci of DAD (Fig. 2, G and H, and fig. S2). The pattern of staining was similar to that in lung tissue from SARS-CoV–infected macaques (positive control). SARS-CoV-2 antigen expression was not observed in any of the syncytia. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 antigen expression was detected in nonlesional tissues of all lung lobes in three out of four macaques (both young and one aged) in a few type I and II pneumocytes, bronchial ciliated epithelial cells, and bronchiolar ciliated epithelial cells. The other aged macaque, without virological or pathological evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the lungs, did have SARS-CoV-2 antigen expression in ciliated epithelial cells of nasal septum (Fig. 2I), nasal concha, and palatum molle, in the absence of associated histopathological changes. No SARS-CoV antigen expression was detected in other sampled tissues, including brain and intestine. To assess the severity of infection with SARS-CoV-2 compared with MERS-CoV, we inoculated young cynomolgus macaques (3 to 5 years of age) with MERS-CoV via the IN and IT route. All animals remained free of clinical signs. At day 21 p.i., all remaining animals (n = 2) seroconverted as revealed by the presence of MERS-CoV–specific antibodies in their sera by ELISA (fig. S3). MERS-CoV RNA was detected in nasal (Fig. 3A) and throat swabs (Fig. 3B) on days 1 to 11 p.i., with peaks on days 1 and 2 p.i., respectively. Low levels [between 1 and 85 median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) equivalent/ml] of MERS-CoV RNA were detected in rectal swabs on days 2 and 3 p.i. Viral RNA was detected in nasal (A) and throat (B) swabs and tissues (C) of MERS-CoV–infected animals by RT-qPCR. Samples from four animals per group were tested. The error bars represent the SEM. Virus was detected in tissues on day 4 by RT-qPCR. Histopathological changes (D) (left) with hypertrophic and hyperplastic type II pneumocytes in the alveolar septa and increased numbers of alveolar macrophages in the alveolar lumina and virus antigen expression (right) in type II pneumocytes. Bar, 50 μm. At autopsy of four macaques at day 4 p.i., three animals had foci of pulmonary consolidation, characterized by slightly depressed areas in the lungs, representing less than 5% of the lung tissue (Table 1). Similar to SARS-CoV-2 infection in both young and aged animals, on day 4 p.i., MERS-CoV RNA was primarily detected in the respiratory tract of inoculated animals (Fig. 3C). Infectious virus titers were comparable to those of SARS-CoV-2 infection, but lower compared to SARS-CoV infection, of young macaques (Table 1). In addition, MERS-CoV RNA was detected in the spleen (Table 1). Table 1 Comparative pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV infections in cynomolgus macaques. Max, maximum; Ref., reference. View this table: Consistent with the presence of virus in the lower respiratory tract at day 4 p.i., histopathological changes characteristic for DAD were observed in the lungs of inoculated animals (Fig. 3D). The alveolar septa were thickened owing to infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages, and to moderate type II pneumocyte hyperplasia and hypertrophy. In the alveolar lumina, there were increased numbers of alveolar macrophages and some edema fluid containing fibrin and some neutrophils (Fig. 3D). Few syncytial cells were seen in the alveolar lumina. MERS-CoV antigen was not detected in tissues on day 4 p.i. in any part of the respiratory tract. We therefore sampled four young macaques at day 1 p.i. At this time, we observed multifocal expression of viral antigen, predominantly in type II pneumocytes and occasionally in type I pneumocytes, bronchiolar and bronchial epithelial cells, and some macrophages (Fig. 3D). In summary, we inoculated young and aged cynomolgus macaques with a low-passage clinical isolate of SARS-CoV-2, which resulted in productive infection in the absence of overt clinical signs. Recent studies in human cases have shown that presymptomatic and asymptomatic cases can also shed virus (14, 15). Increased age did not affect disease outcome, but there was prolonged viral shedding in the upper respiratory tract of aged animals. Prolonged shedding has been observed in both SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV patients (16, 17). SARS-CoV-2 shedding in our asymptomatic model peaked early in the course of infection, similar to what is seen in symptomatic patients (16). Also, SARS-CoV-2 antigen was detected in ciliated epithelial cells of nasal mucosae at day 4 p.i., which was not seen for SARS-CoV (10) or MERS-CoV infections (this study) in this animal model. Viral tropism for the nasal mucosa fits with efficient respiratory transmission, as has been seen for influenza A virus (18). This early peak in virus shedding for SARS-CoV-2 is similar to that of influenza virus shedding (19) and may explain why case detection and isolation may not be as effective for SARS-CoV-2 as it was for the control of SARS-CoV (20). SARS-CoV-2 was primarily detected in tissues of the respiratory tract; however, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was also detectable in other tissues such as intestines, in line with a recent report (21). Similar results regarding viral shedding and tissue and cell tropism were recently also reported after SARS-CoV-2 inoculation in rhesus macaques. However, unlike in our model, SARS-CoV-2 infection in rhesus macaques does result in transient respiratory disease and weight loss (22, 23). Two out of four animals had foci of DAD on day 4 p.i. The colocalization of SARS-CoV-2 antigen expression and DAD provides strong evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection caused this lesion. The histological character of the DAD, including alveolar and bronchiolar epithelial necrosis, alveolar edema, hyaline membrane formation, and accumulation of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes, corresponds with the limited pathological analyses of human COVID-19 cases (6, 7). In particular, the presence of syncytia in the lung lesions is characteristic of respiratory coronavirus infections. Whereas MERS-CoV primarily infects type II pneumocytes in cynomolgus macaques, both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 also infect type I pneumocytes. Injury to type I pneumocytes can result in pulmonary edema, and formation of hyaline membranes (24), which may explain why hyaline membrane formation is a hallmark of SARS and COVID-19 (7, 10) but not frequently reported for MERS (25, 26). These data show that cynomolgus macaques are permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection, shed virus for a prolonged period of time, and display COVID-19–like disease. In this nonhuman primate model, SARS-CoV-2 replicates efficiently in respiratory epithelial cells throughout the respiratory tract, including nasal cavity, bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli. Replication in the upper respiratory tract fits with efficient transmission between hosts, whereas replication in the lower respiratory tract fits with the development of lung disease. An in-depth comparison of infection with SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 in this model may identify key pathways in the pathogenesis of these emerging viruses. This study provides a new infection model that will be critical in the evaluation and licensure of preventive and therapeutic strategies against SARS-CoV-2 infection for use in humans, as well as for evaluating the efficacy of repurposing species-specific existing treatments, such as pegylated interferon (12). Supplementary MaterialsAcknowledgments: We thank L. de Meulder, A. van der Linden, I. Chestakova, and F. van der Panne for technical assistance. We also thank Y. Kap, D. Akkermans, V. Vaes, M. Sommers, and F. Meijers for assistance with the animal studies. Funding: This research is (partly) financed by the NWO Stevin Prize awarded to M.K. by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), H2020 grant agreement 874735-VEO to M.K., NIH/NIAID contract HHSN272201400008C to R.F., and H2020 grant agreement 101003651–MANCO to B.H. Author contributions: Conceptualization, B.R., T.K., R.F., M.K., RdS, M.F. B.H.; investigation, B.R., T.K., S.H., T.B., M.L., D.d.M., G.v.A., J.v.d.B., N.O., D.S., P.v.R., L.L.; resources, B.H., C.D., E.V., B.V., J.L.; supervision, B.R. and B.H.; writing, original draft, B.R., T.K., and B.H.; writing–review and editing, all authors; funding acquisition: S.H., B.H., R.F., and M.K. Animal welfare: Research was conducted in compliance with the Dutch legislation for the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (2014, implementing EU Directive 2010/63) and other relevant regulations. The licensed establishment where this research was conducted (Erasmus MC) has an approved OLAW Assurance no. A5051-01. Research was conducted under a project license from the Dutch competent authority and the study protocol (no. 17-4312) was approved by the institutional Animal Welfare Body. Competing interests: T.B., R.F., and B.H. are listed as inventors on a patent application related to MERS-coronavirus diagnostics, therapy and vaccines. Other authors declare no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This license does not apply to figures/photos/artwork or other content included in the article that is credited to a third party; obtain authorization from the rights holder before using such material. |

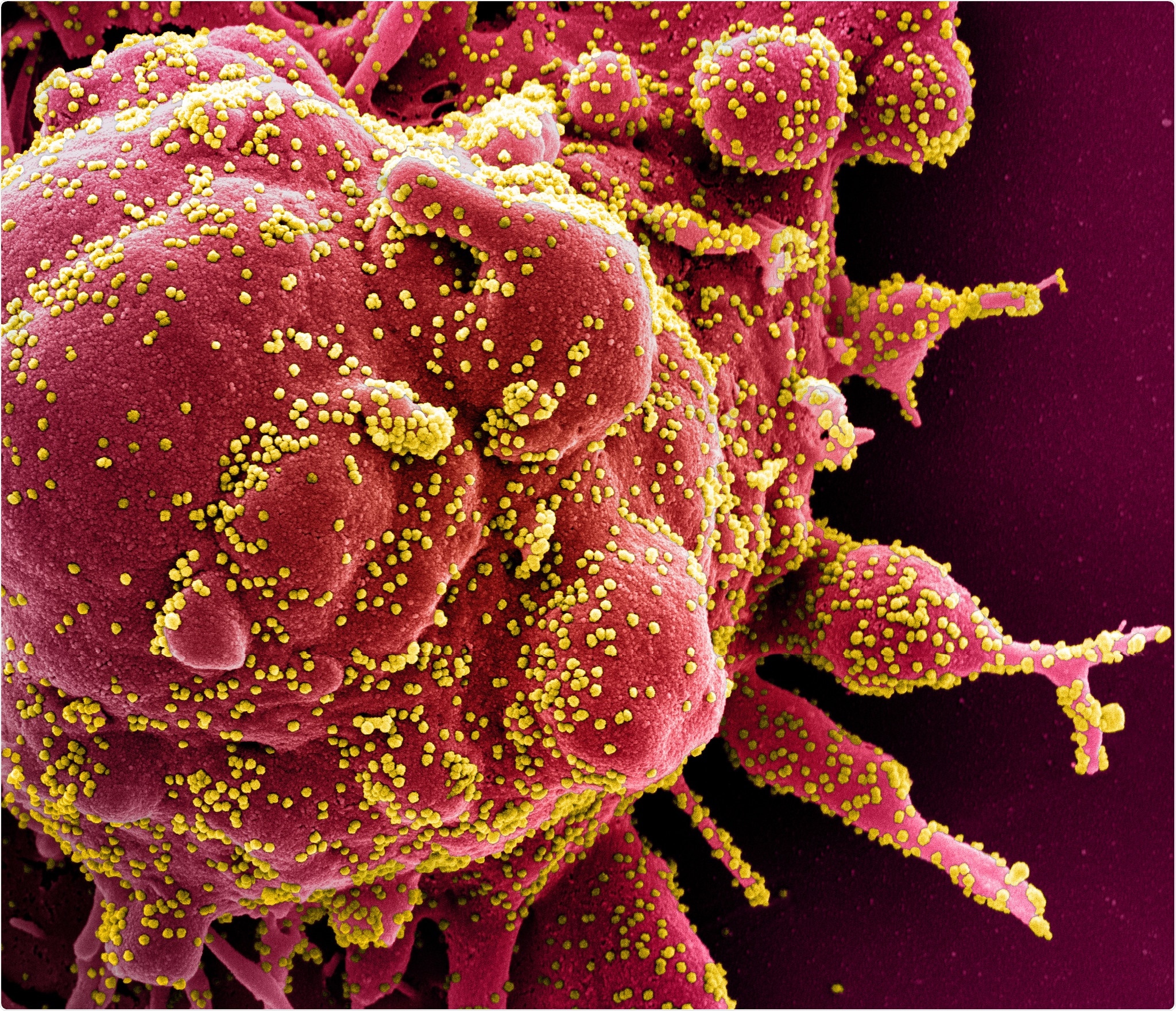

| No specific COVID-19-linked lesions found despite extensive organ injury - News-Medical.Net Posted: 31 May 2020 09:14 PM PDT A recent paper published online on the preprint server medRxiv* in May 2020 reports autopsy results on COVID-19 patients. The paper concludes that there were no specific hallmark lesions of COVID-19 in any of the many organs found to be injured by the infection in patients who died of the disease. How Was the Study Done?In a bid to understand the disease process caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), investigators have been trying to understand how the virus causes severe injury and sometimes death in a large percentage of cases. The researchers examined 17 adults, of median age 72 years, of which 12 were males. The median duration from hospitalization to death was 13 days.  Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 Colorized scanning electron micrograph of an apoptotic cell (red) heavily infected with SARS-COV-2 virus particles (yellow), isolated from a patient sample. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID Except for 2 patients, all had one or more co-existing medical conditions, most commonly diabetes, and high blood pressure, at 9 and 10 patients, respectively. Another 4 each had cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, and cancer. Eleven and six patients died in the intensive care unit and the medical ward, respectively, with the chief causes of death being recorded as a respiratory failure in 9 cases and multiple organ failure in 7 cases. What Did the Study Show?Macroscopic examination of the lungs on autopsy showed a variety of findings, from heavy consolidated lungs to pulmonary artery thrombi. The heart was significantly larger than usual, and the liver in a few patients as well. The kidneys were also larger in many patients, and looked pale but had no signs of blocked blood flow or hemorrhage. The gut was nonspecific, while the brain samples mostly showed no pathology. On histologic examination, the findings varied from diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) in the lungs, with microscopic clots within the small pulmonary arteries, acute pneumonic changes or bronchopneumonia, to chronic ischemic heart damage in a majority of patients, to congestive liver disease and fatty liver. The brain was hemorrhagic or suffused in about half the patients, but chronic changes were also frequently seen. Of the 17 patients, 11 had the virus in their lungs when examined by immunohistochemistry, but in 16 by RT-PCR, which is more sensitive. The researchers failed to observe any uniform pattern of distribution of the virus in the lungs. At least one organ in every patient contained viral particles, mostly in the lungs, heart, liver, intestines, and a little less frequently in the spleen, kidney, and brain. The viral load was higher for tissues other than the lung. Difficulties in Identifying a Specific Pattern of COVID-19 InjuryThe aim of the study was to identify SARS-CoV-2-related organ injury. However, the autopsy results in these 17 patients showed signs of chronic disease overlaid by a variety of more recent signs. With gross differences in the co-morbidity pattern, treatment protocols, adoption of mechanical ventilation, and presence of acute complications, there is bound to be a diverse representation of lung injury. For instance, in the case of DAD, it could have been part of the natural course of COVID-19 or alternatively, a result of other complications like hospital-acquired pneumonia. These are hard to differentiate in such critically ill patients, with over half of them showing acute pneumonic changes. However, earlier researchers did conclude that COVID-19 pneumonia is not linked to DAD but to acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia (AFOP). On the other hand, it is possible that AFOP could be a form of DAD that produces more fibrin. The hyaline membranes characteristic of AFOP is also seen in DAD but with an unpredictable distribution. Thus, the whole lung must be examined to rule out the latter. Again, with lung biopsies, the presence of the virus could be missed in as many as half the cases. The study thus shows the potential error inherent in relying on lung biopsies and not whole lung studies to deduce the effects of this infection. Pulmonary embolism was not very common, though microthrombi were seen frequently. Seven patients had either PE or pulmonary infarction; however, it was not the primary or major cause of death in this series of patients. Microthrombi are seen in many cases of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), and are a nonspecific feature of procoagulative and inflammatory states. Acute cardiac injury was also not very common in the form of acute myocarditis or myocardial ischemia. The presence of the virus in all the tissues examined may reflect the widespread presence of the ACE2 receptor in the body and not direct viral injury.

Limitations and ImplicationsThe study is limited in that only 17 patients were included, and the post-mortem examinations could be performed only 72-96 hours after death. This allowed significant autolysis to occur, leading to the destruction of tissues like the gut and kidneys. Another issue was the difficulty of tracing the timeline of viral spread between different organs, which might have helped to generate a theory as to the route of spread of the virus from the lungs to other parts of the body. Finally, the course of the disease, the time to death, and the type of treatment was widely different, meaning that the findings could not be mapped to the microscopic findings as being results of COVID-19 itself, nor could the actual mechanism of organ injury be deciphered. The absence of a specific pattern of injury in organs other than the lungs suggests that "SARS-CoV-2 infection may be just the trigger for an overwhelming host response, which could secondarily result in COVID-19-associated organ dysfunction." Secondly, the detection of viral nucleic acid by the RT-PCR test need not mean the presence of actively replicating virus or even the presence of viral infection in the cell itself, but instead could be an innocuous finding. The study, therefore, highlights the danger of mapping any single extrapulmonary feature of injury to COVID-19, while confirming the presence of the virus in every organ irrespective of whether lesions were seen on microscopic examination. *Important NoticemedRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information. Journal reference: |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "what is respiratory distress,what is sars,what is sars virus" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment