“Diagnostic Testing for SARS–CoV-2 - Annals of Internal Medicine” plus 2 more

“Diagnostic Testing for SARS–CoV-2 - Annals of Internal Medicine” plus 2 more |

- Diagnostic Testing for SARS–CoV-2 - Annals of Internal Medicine

- Coronavirus: Comparing COVID-19, SARS and MERS - Al Jazeera English

- Coronaviruses – A Brief History - Snopes.com

| Diagnostic Testing for SARS–CoV-2 - Annals of Internal Medicine Posted: 13 Apr 2020 12:04 PM PDT McGill University Health Centre and McGill Interdisciplinary Initiative in Infection and Immunity, Montreal, Quebec, Canada (M.P.C.) McGill Interdisciplinary Initiative in Infection and Immunity and Montreal Children's Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada (J.P.) Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, and Centre Hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada (M.D.) Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, Massachusetts (S.K.) CHU Sainte-Justine, Université de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada (C.Q.) McGill University Health Centre, McGill Interdisciplinary Initiative in Infection and Immunity, and McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada (M.L., C.P.Y.) Foundation of Innovative New Diagnostics, Malaria and Fever Program, Geneva, Switzerland, and University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom (S.D.) Acknowledgment: The authors thank Professor Ellen Jo Baron for insightful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript and Ms. Chelsea Caya for assistance with literature searches and assembling figures. Grant Support: Drs. Papenburg, Quach, and Yansouni have received career awards from the Québec Health Research Fund. Disclosures: Dr. Cheng reports grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research and McGill Interdisciplinary Initiative in Infection and Immunity during the conduct of the study; after the manuscript was written and submitted, he was offered a position on the scientific advisory board of GEn1E Lifesciences, but this position is unrelated to the submitted work. Dr. Papenburg reports grants and personal fees from BD Diagnostics, Seegene, and AbbVie; personal fees from Cepheid; and grants from MedImmune, Sanofi Pasteur, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Hoffman–La Roche outside the submitted work. Dr. Kanjilal reports grants from PhAST Diagnostics outside the submitted work. Dr. Libman reports grants from GeoSentinel Network outside the submitted work. Dr. Yansouni reports nonfinancial support from bioMérieux outside the submitted work. Authors not named here have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Disclosures can also be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M20-1301. Editors' Disclosures: Christine Laine, MD, MPH, Editor in Chief, reports that her spouse has stock options/holdings with Targeted Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Darren B. Taichman, MD, PhD, Executive Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interests to disclose. Cynthia D. Mulrow, MD, MSc, Senior Deputy Editor, reports that she has no relationships or interests to disclose. Jaya K. Rao, MD, MHS, Deputy Editor, reports that she has stock holdings/options in Eli Lilly and Pfizer. Christina C. Wee, MD, MPH, Deputy Editor, reports employment with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Sankey V. Williams, MD, Deputy Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interests to disclose. Yu-Xiao Yang, MD, MSCE, Deputy Editor, reports that he has no financial relationships or interest to disclose. Corresponding Author: Matthew P. Cheng, MDCM, Division of Infectious Diseases, McGill University Health Centre, 1001 Decarie Boulevard, E05.1709, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H4A 3J1; e-mail, matthew.cheng@mcgill.ca. Current author addresses and author contributions are available at Annals.org. Current Author Addresses: Dr. Cheng, MDCM, Division of Infectious Diseases, McGill University Health Centre, 1001 Decarie Boulevard, E05.1709, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H4A 3J1. Dr. Papenburg: Division of Infectious Diseases, Montreal Children's Hospital, 1001 Decarie Boulevard, E05.1905, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H4A 3J1. Dr. Desjardins: Division of Transplant Infectious Disease, Brigham and Women's Hospital, 75 Francis Street, PBB-A4, Boston, MA 02115. Dr. Kanjilal: Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, 401 Park Drive, Suite 401, East Boston, MA 02115. Dr. Quach: Divison of Infectious Diseases, CHU Sainte-Justine, 3175, ch. Côte Ste-Catherine, B.17.102, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3T 1C5. Dr. Libman: Division of Infectious Diseases, McGill University Health Centre, 1001 Decarie Boulevard, E05.1830, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H4A 3J1. Dr. Dittrich: Foundation of Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND), Campus Biotech, Chemin des Mines 91 202, Geneva, Switzerland. Dr. Yansouni: Division of Infectious Diseases, McGill University Health Centre, 1001 Decarie Boulevard, EM3.3242, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H4A 3J1. Author Contributions: Conception and design: M.P. Cheng, J. Papenburg, M. Desjardins, M. Libman, S. Dittrich, C.P. Yansouni. Analysis and interpretation of the data: M.P. Cheng, J. Papenburg, S. Dittrich, C.P. Yansouni. Drafting of the article: M.P. Cheng, J. Papenburg, M. Desjardins, S. Kanjilal, M. Libman, S. Dittrich, C.P. Yansouni. Critical revision for important intellectual content: M.P. Cheng, J. Papenburg, M. Desjardins, S. Kanjilal, C. Quach, M. Libman, C.P. Yansouni. Final approval of the article: M.P. Cheng, J. Papenburg, M. Desjardins, S. Kanjilal, C. Quach, M. Libman, S. Dittrich, C.P. Yansouni. Obtaining of funding: C.P. Yansouni. Administrative, technical, or logistic support: C.P. Yansouni. Collection and assembly of data: M.P. Cheng, J. Papenburg, C.P. Yansouni. |

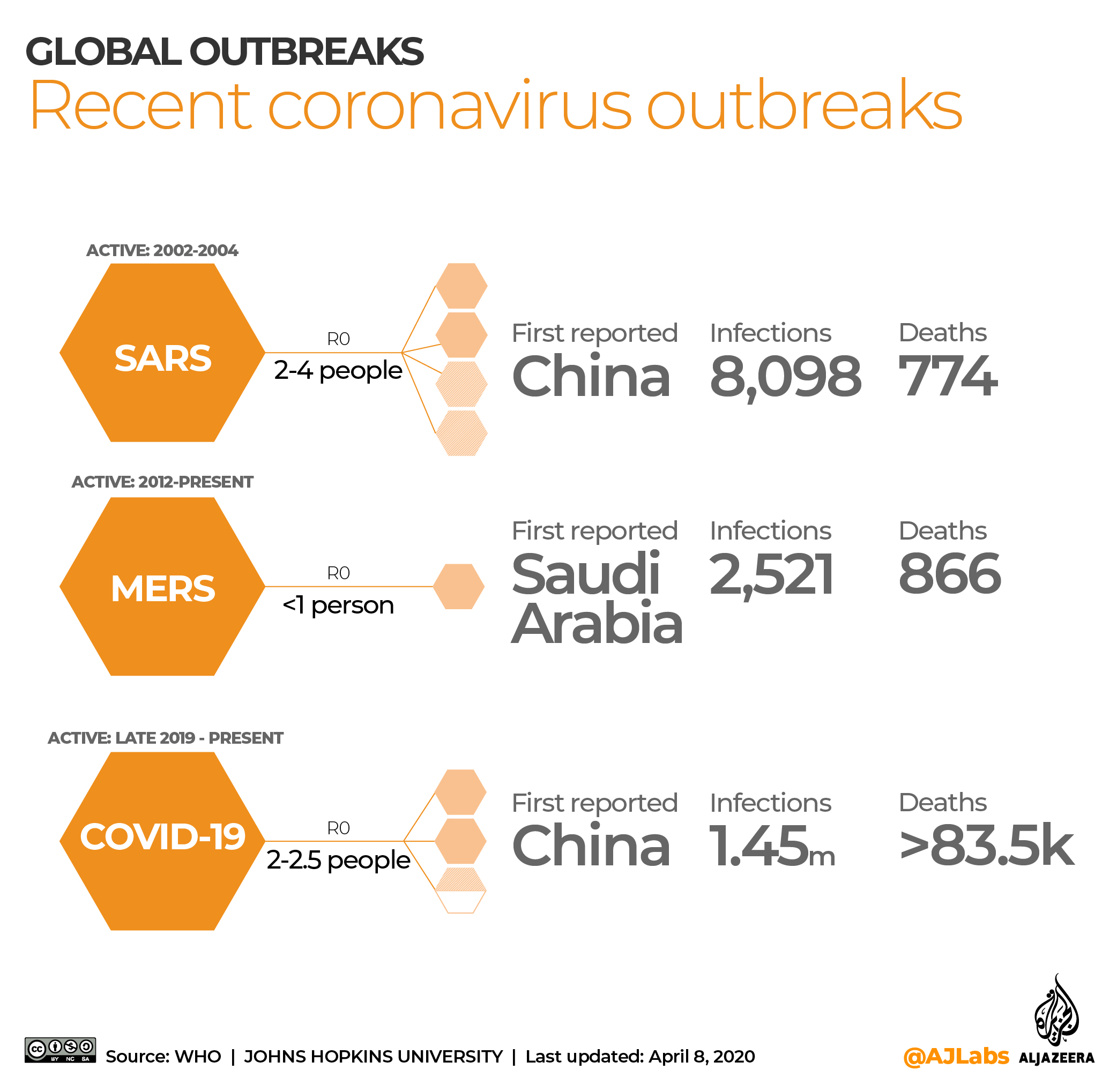

| Coronavirus: Comparing COVID-19, SARS and MERS - Al Jazeera English Posted: 08 Apr 2020 09:21 AM PDT The new coronavirus outbreak has spread rapidly around the world, affecting more than 183 countries and territories, infecting over a million and killing more than 80,000 people. It is reported to have emerged in China's Hubei province late last year. On March 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of the coronavirus a pandemic, which it defines as "global spread of a new disease". More:Governments have imposed tough measures, including travel restrictions and curfews, to contain the spread of the virus as scientists worldwide race to find a vaccine. This is not the first time an international health crisis occurred due to the spread of a novel coronavirus or other zoonotic (animal-originated) viruses, such as influenza that created the swine, bird and seasonal flu epidemics in recent history. Seasonal flu alone is estimated to result in three to five million cases of severe illness, and 290,000 to 650,000 respiratory deaths annually. Here is a comparison of the information and data we have on COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, with similar recent coronavirus-related diseases. COVID-19As of April 7, 2020, the number of global COVID-19 cases was more than 1,290,000 with over 76,000 deaths. While a few regions, such as China's Hubei province and South Korea, report falling numbers of new local cases, the number of infections keeps rising across the world. Although the source of the virus is suggested to be animals, the specific species is yet to be confirmed. The main symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, tiredness and dry cough, the WHO said, adding that some patients may have aches and pains, nasal congestion, runny nose, sore throat or diarrhoea. According to the WHO, approximately one out of every six infected people becomes seriously ill and develops difficulty in breathing. The R0 (pronounced R-naught), is a mathematical term to measure how contagious and reproductive an infectious disease is as it displays the average number of people that will be infected from a contagious person. The WHO puts the R0 of COVID-19 at 2 to 2.5. SARSSevere acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), also caused by a coronavirus, was first reported in November 2002 in the Guangdong province of southern China. The viral respiratory illness spread to 29 countries across multiple continents before it was contained in July the following year. Between its emergence and May 2014, when the last case was reported, 8,098 people were infected and 774 of them died. Various studies and the WHO suggest that the coronavirus that caused SARS originated from bats, and it was transmitted to humans through an intermediate animal - civet cats. Symptoms of SARS are flu-like, such as fever, malaise, myalgia, headache, diarrhoea, and shivering. No other additional symptom has proved to be specific for the diagnosis of SARS. The R0 of SARS is estimated to range between 2 and 4, averaging at 3, meaning it is highly contagious. MERSThe Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a still active viral respiratory disease first identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012. Approximately 80 percent of human cases were reported by the kingdom, but it has been reported in 27 countries. As of March 2020, 2,521 MERS cases were confirmed globally with 866 deaths due to the illness, mainly in Saudi Arabia. According to WHO, dromedary camels are a large reservoir host for MERS and an animal source of MERS infection in humans. However, human cases of MERS infections have been predominantly caused by human-to-human transmissions. MERS might show no symptoms, mild respiratory symptoms or severe acute respiratory disease and death. Fever, cough and shortness of breath are common symptoms. If it gets severe, it might cause respiratory failure that requires mechanical ventilation. R0 of MERS is lower than one, identifying it as it is a mildly contagious disease. |

| Coronaviruses – A Brief History - Snopes.com Posted: 15 Apr 2020 09:21 AM PDT This article is republished here with permission from The Conversation. This content is shared here because the topic may interest Snopes readers; it does not, however, represent the work of Snopes fact-checkers or editors. Most of us will be infected with a coronavirus at least once in our life. This might be a worrying fact for many people, especially those who have only heard of one coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, the cause of the disease known as COVID-19. There is much more to coronaviruses than SARS-CoV-2. Coronaviruses are actually a family of hundreds of viruses. Most of these infect animals such as bats, chickens, camels and cats. Occasionally, viruses that infect one species can mutate in such a way that allows them to start infecting another species. This is called "cross-species transmission" or "spillover". The first coronavirus was discovered in chickens in the 1930s. It was a few decades until the first human coronaviruses were identified in the 1960s. To date, seven coronaviruses have the ability to cause disease in humans. Four are endemic (regularly found among particular people or in a certain area) and usually cause mild disease, but three can cause much more serious and even fatal disease.

Pieter/Shutterstock Common coldCoronaviruses can be found all over the world and are responsible for about 10-15% of common colds, mostly during the winter. The coronaviruses that cause mild to moderate disease in humans are called: 229E, OC43, NL63 and HKU1. The first coronaviruses discovered that are able to infect humans are 229E and OC43. Both of these viruses usually result in the common cold and rarely cause severe disease on their own. They are often detected at the same time as other respiratory infections. When several viruses, or viruses and bacteria, are found in patients this is called co-infection and can result in more severe disease. In 2004, NL63 was detected for the first time in a baby suffering from bronchiolitis (a lower respiratory tract infection) in the Netherlands. This virus has probably been around for hundreds of years, we just hadn't found it until then. A year later, in Hong Kong, another coronavirus was found – this time in an elderly patient with pneumonia. It was later named HKU1 and has been found to be present in populations around the world. Deadlier strainsBut not all coronaviruses cause mild disease. Sars (severe acute respiratory syndrome) caused by SARS-CoV was first detected in November 2002. The cause of this outbreak wasn't confirmed until 2003 when the genome of the virus was identified by Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory. Sars bears many similarities to the current pandemic of COVID-19. Older people were much more likely to suffer severe disease and symptoms included fever, cough, muscle pain and sore throat. But there was a much greater chance of dying if you had Sars. From 2002 until the last reported case in 2014, 774 people died. A decade later, in 2012, there was another outbreak involving a newly identified coronavirus: MERS-CoV. The first case of Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers) occurred in Saudi Arabia. There were two further Mers outbreaks: South Korea in 2015 and Saudi Arabia in 2018. There are a handful of Mers cases every year, but the outbreaks are usually well contained. So why did Sars or Mers not result in pandemics? The R0 of both Sars and SARS-CoV-2 is about two or three (although some more recent estimates of the R0 for SARS-CoV-2 are around five), meaning that every infected person is likely to infect two or three other people. The symptoms of Sars were more severe, so it was much easier to identify and isolate patients. The R0 of Mers is below one. It is not very contagious. Most of the cases have been linked to close contact with infected camels or very close contact with an already infected person. One of the main challenges in containing the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak is that symptoms can be very mild – some people may not even show any symptoms at all – but can still infect other people. SARS-CoV-2 is not as deadly as either Sars or Mers, but because it can spread undetected, the numbers of people it will infect and the numbers that will die will be higher than any coronavirus we have ever encountered. So please, stay at home. Lindsay Broadbent, Research Fellow, School of Medicine, Dentistry and Biomedical Sciences, Queen's University Belfast This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "sars transmission,sars treatment,sars virus origin" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment