“Coronavirus: Scotland drug trials to treat respiratory damage - Daily Mail” plus 2 more

“Coronavirus: Scotland drug trials to treat respiratory damage - Daily Mail” plus 2 more |

- Coronavirus: Scotland drug trials to treat respiratory damage - Daily Mail

- 'Silent hypoxia' may be killing COVID-19 patients. But there's hope. - Livescience.com

- Three Ways to Make Coronavirus Drugs In a Hurry - Scientific American

| Coronavirus: Scotland drug trials to treat respiratory damage - Daily Mail Posted: 23 Apr 2020 09:44 AM PDT Scotland will soon begin its first clinical trial of a drug to treat the severe respiratory damage caused by lung inflammation in COVID-19 patients. Researchers from the University of Dundee will conduct trials of brensocatib — formerly known as INS1007 — to tackle lung inflammation caused by the virus. Although COVID-19 infections are mild in most people, up to 20 per cent of patients develop lung inflammation and may end up needing a ventilator to breathe. It is the body's own inflammatory response — designed to clear the virus — which causes the lung damage that can even lead to respiratory failure and death. Scroll down for video  Scotland will soon begin its first clinical trial of a drug to treat the severe respiratory damage caused by lung inflammation in COVID-19 patients. Researchers from the University of Dundee will conduct trials of brensocatib to tackle lung inflammation caused by the virus As part of the STOP-COVID19 trial, the team will explore whether brensocatib can reduce the incidence of acute lung injury and the need for mechanical ventilation. It is hoped that the treatment will lead to patients spending fewer days dependent on oxygen and less time in hospital, reducing the burden on healthcare systems. STOP-COVID19 is one of the studies into the novel coronavirus that has been given urgent public health research status by the Department of Health and Social Care. Trials conducted to date have shown that brensocatib reduces inflammation in the lungs of people with underlying lung conditions — so it is hoped that the drug will have a similarly beneficial effect in those suffering from COVID-19. Beginning in early May, the university will recruit 300 volunteers from ten hospitals across the UK. Patients will be offered the chance to participate immediately after receiving a positive diagnosis for coronavirus. Half this number will receive brensocatib in addition to standard hospital care, while the other half will receive a placebo instead. 'High rates of patients requiring ventilation and overwhelming intensive care unit capacity has been a major cause of excess deaths around the world,' said lead researcher James Chalmers of the University of Dundee. 'We hope that brensocatib can put a brake on the devastation this disease causes — to literally stop COVID-19 when it begins attacking the lungs,' added Professor Chalmers, who is also a respiratory physician at Ninewells Hospital, a trial site. 'The medical community has never faced a more urgent need for treatment than the unprecedented situation we face today with COVID-19.' 'The mechanism of action of brensocatib observed in a study in bronchiectasis patients provides a strong rationale for evaluating this novel treatment candidate in other neutrophil-driven inflammatory conditions.' 'It is my hope that it will have applicability in patients at risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome — a devastating outcome of COVID-19 for which there are currently no approved therapies.' The Dundee researchers will be teaming up with the US-based biopharmaceutical company Insmed, at which Martina Flammer is chief medical officer.  Although COVID-19 infections are mild in most people, up to 20 per cent of patients develop lung inflammation and may end up needing a ventilator to breathe. It is the body's own inflammatory response — designed to clear the virus — which causes the lung damage that can even lead to respiratory failure and death 'The global COVID-19 pandemic has generated an extraordinary response from the biopharmaceutical industry to bring to bear all potential means of fighting this disease and preventing its most severe outcomes,' Dr Flammer said. 'At the start of the outbreak, Insmed began pursuing an in vivo mouse model to better understand the potential of brensocatib in preventing acute respiratory distress syndrome.' 'We are very pleased to support Professor James Chalmers and the University of Dundee in leading a controlled clinical trial that will help us evaluate the potential impact of brensocatib on hospitalised patients suffering from severe COVID-19.' 'This is the first Scottish-led drug trial into COVID-19 and it has been prioritised and designated as an urgent public health study,' added study investigator and NHS Tayside R&D director Jacob George. 'Tayside can be justifiably proud of this and we look forward to collaborating with other NHS Boards in Scotland to recruit eligible patients onto the trial.'

|

| Posted: 23 Apr 2020 08:30 AM PDT  As doctors see more and more COVID-19 patients, they are noticing an odd trend: Patients whose blood oxygen saturation levels are exceedingly low but who are hardly gasping for breath. These patients are quite sick, but their disease does not present like typical acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a type of lung failure known from the 2003 outbreak of the SARS coronavirus and other respiratory diseases. Their lungs are clearly not effectively oxygenating the blood, but these patients are alert and feeling relatively well, even as doctors debate whether to intubate them by placing a breathing tube down the throat. The concern with this presentation, called "silent hypoxia," is that patients are showing up to the hospital in worse health than they realize. But there might be a way to prevent that, according to a New York Times Op-Ed by emergency department physician Richard Levitan. If sick patients were given oxygen-monitoring devices called pulse oximeters to monitor their symptoms at home, they might be able to seek medical treatment sooner, and ultimately avoid the most invasive treatments. Related: Are ventilators being overused on COVID-19 patients? "This is not a new phenomenon," said Dr. Marc Moss, the division head of Pulmonary Sciences and Critical Care Medicine at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. There are other conditions in which patients are extremely low on oxygen but don't feel any sense of suffocation or lack of air, Moss told Live Science. For example, some congenital heart defects cause circulation to bypass the lungs, meaning the blood is poorly oxygenated. However, the increased understanding that people with COVID-19 may show up with these atypical coronavirus symptoms is changing the way doctors treat them. Gasping for airNormal blood-oxygen levels are around 97%, Moss said, and it becomes worrisome when the numbers drop below 90%. At levels below 90%, the brain may not get sufficient oxygen, and patients might start experiencing confusion, lethargy or other mental disruptions. As levels drop into the low 80s or below, the danger of damage to vital organs rises. However, patients may not feel in as dire straits as they are. A lot of coronavirus patients show up at the hospital with oxygen saturations in the low 80s but look fairly comfortable and alert, said Dr. Astha Chichra, a critical care physician at Yale School of Medicine. They might be slightly short of breath, but not in proportion to the lack of oxygen they're receiving. There are three major reasons people feel a sense of dyspnea, or labored breathing, Moss said. One is something obstructing the airway, which is not an issue in COVID-19. Another is when carbon dioxide builds up in the blood. A good example of that phenomenon is during exercise: Increased metabolism means more carbon dioxide production, leading to heavy breathing to exhale all that CO2. Related: Could genetics explain why some COVID-19 patients fare worse than others? A third phenomenon, particularly important in respiratory disease, is decreased lung compliance. Lung compliance refers to the ease with which the lungs move in and out with each breath. In pneumonia and in ARDS, fluids in the lungs fill microscopic air sacs called alveoli, where oxygen from the air diffuses into the blood. As the lungs fill with fluid, they become more taut and stiffer, and the person's chest and abdominal muscles must work harder to expand and contract the lungs in order to breathe. This happens in severe COVID-19, too. But in some patients, the fluid buildup is not enough to make the lungs particularly stiff. Their oxygen levels may be low for an unknown reason that doesn't involve fluid buildup — and one that doesn't trigger the body's need to gasp for breath. Coronavirus science and newsWorking to breatheExactly what is going on is yet unknown. Chichra said that some of these patients might simply have fairly healthy lungs, and thus have the lung compliance (or elasticity) — so not much resistance in the lungs when a person inhales and exhales — to feel like they are not short on air even as their lungs become less effective at diffusing oxygen into the blood. Others, especially geriatric patients, might have comorbidities that mean they live with low oxygen levels regularly, so they're used to feeling somewhat lethargic or easily winded, she said. Related: 11 surprising facts about the respiratory system In the New York Times Op-Ed on the phenomenon, Levitan wrote that the lack of gasping might be due to a particular phase of the lung failure caused by COVID-19. When the lung failure first starts, he wrote, the virus may attack the lung cells that make surfactant, a fatty substance in the alveoli, which reduces surface tension in the lungs, increasing their compliance. Without surfactant, the increased surface tension causes the alveoli to deflate, but if they are not filled with fluid,, they won't feel stiff, Levitan wrote. This could explain how the alveoli fail to oxygenate the blood without the patient noticing the need to gasp for more air. The virus might also create hypoxia by damaging the blood vessels that lead to the lungs, Moss said. Normally, when a patient has pneumonia, the tiny blood vessels around the fluid-filled areas of the lungs constrict (called hypoxic vasoconstriction): Sensing a lack of oxygen in the damaged areas, the body shunts blood to other, healthier parts of the lungs. Because pneumonia fills the lungs with fluid, the person will feel starved for air and gasp for breath. But their vessels send the blood to the least-damaged parts of the lung, so their blood oxygenation stays relatively high, given the damage. In COVID-19, that balance may be off. The lungs aren't very fluid-filled and stiff, but the blood vessels don't constrict and reroute blood to the least-damaged spots. People feel free to inhale and exhale without resistance, but the blood is still trying to pick up oxygen at alveoli that are damaged and inefficient. "What is most likely happening here is that hypoxic vasoconstriction is lost for some reason, so that blood does flow to places where there is some damage to the lungs," Moss said. It could also be a combination of factors, he added. "I'm not going to say the alveoli are normal and the surfactant is normal, but when someone has hypoxia out of proportion to what you would see in the lung, that makes lung specialists think there is a problem on the blood vessel side," he said. In the New York Times, Levitan suggests that patients who are not sick enough to be admitted to the hospital be given pulse oximeters, devices that clamp to the finger to measure blood oxygenation. If their oxygenation numbers start to fall, it could be an early warning sign to seek medical treatment. "It's an intriguing possibility," Moss said. Even without widespread at-home oxygen monitoring, doctors are now starting to differentiate between patients who have low oxygen levels and who are working hard to breathe, and those who have low oxygen levels but are breathing without distress, Chichra said. Early in the pandemic, knowing that COVID-19 patients can start to fail quickly, physicians tended to put people with hypoxia on ventilators quickly. Now, Chichra said, it's becoming clear that patients who aren't struggling for breath often recover without being intubated. They may do well with oxygen delivered via nasal tube or a non-rebreather mask, which fits over the face to deliver high concentrations of oxygen. Hypoxic patients who are breathing quickly and laboriously, with elevated heart rates, tend to be the ones who need mechanical ventilation or non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation, Chichra said. The latter is a method that uses a face mask instead of a tube down the throat, but also uses pressure to push air into the lungs. "The key difference we've found between these folks is that the people who are working hard to breathe are the folks who usually need to be intubated," Chichra said. Originally published on Live Science. |

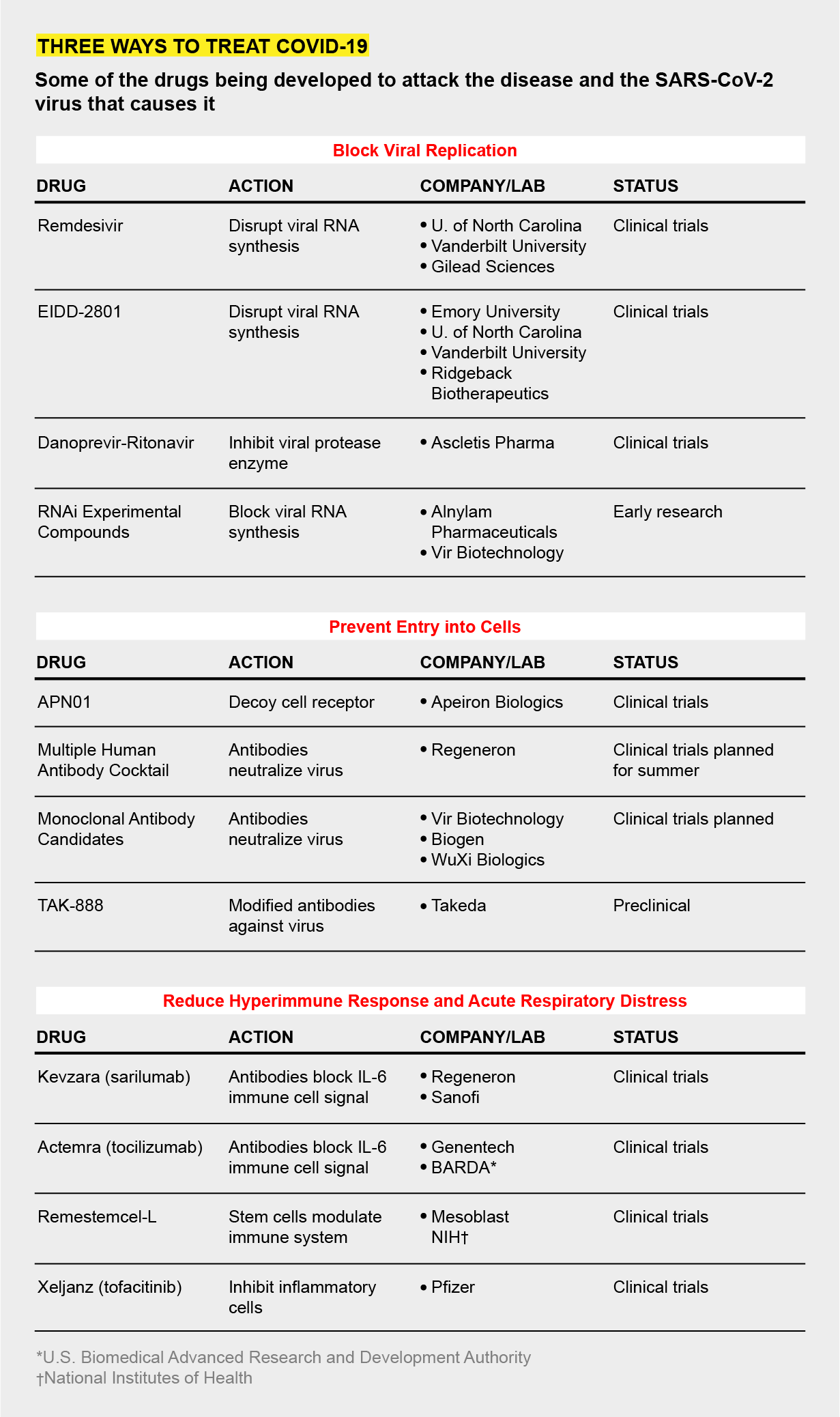

| Three Ways to Make Coronavirus Drugs In a Hurry - Scientific American Posted: 23 Apr 2020 04:44 AM PDT Mark Denison began hunting for a drug to treat COVID-19 almost a decade before the contagion, driven by a novel coronavirus, devastated the world this year. Denison is not a prophet, but he is a virologist and an expert on the often deadly coronavirus family, members of which also caused the SARS outbreak in 2002 and the MERS eruption in 2012. It is a big viral group, and "we were pretty certain another one would soon emerge," says Denison, who directs the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. A virus is an unusual beast. Essentially it is a cluster of genetic material that integrates itself into a cell and takes over some of the cell's molecular machinery, using it to assemble an army of viral copies. Those clones burst out of the cell, destroying it, and go on to infect nearby cells. Viruses are hard to kill off completely because of their cellular integration—they hide within their hosts. And they have explosive reproductive rates. Because total eradication is so hard, antiviral drugs instead aim to limit replication to low levels that cannot hurt the body. In 2013 Denison and Ralph Baric, a coronavirus researcher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, identified a vulnerable site on a protein common to all coronaviruses they had examined, a spot that is key to the microbe's ability to make copies of itself. If that ability is hindered, a coronavirus cannot cause widespread infection. Four years later researchers in the two laboratories spotted a compound that acted on this protein site. It was sitting, unused, in a large library of antiviral compounds created by the biotech giant Gilead Biosciences. The scientists got a sample and, in test tube and animal experiments, showed that the drug, called remdesivir, shut down the replicating machinery of several coronavirus variants. So in early January, when the alarms rang about SARS-CoV-2, Denison and Baric alerted colleagues at Gilead that they were sitting on a potential treatment. Largely because of its activity against other coronavirus strains in Denison and Baric's animal studies, remdesivir was made available to patients for "compassionate use" in January. By March, Gilead had rushed the compound into two human trials, planning to test the drug's safety and most effective doses on about 1,000 ill patients over several months; health authorities in China began two similar trials. While that was happening, Denison, Baric and a group of their colleagues at Emory University identified still another compound, called EIDD-2801, that hits the same viral vulnerability. In early April they published results showing that in mice, the new substance helped breathing and reduced the amount of many coronaviruses. In test-tube experiments with human lung cells, it drastically hindered SARS-CoV-2. Several labs around the world, like Denison's and Baric's, have logged years of experience poking about the inner workings of coronaviruses because of SARS and MERS. By the time the new coronavirus was genetically sequenced and its structure revealed, scientists already had identified the enzymes and proteins that most coronaviruses use to spread from one infected human cell to another and also understood that the body could create an overly aggressive inflammatory response when the virus infected lung airway cells. Because of this work, three main strategies for impeding the virus have emerged as the labs have turned to the current threat. One strategy is to find compounds like remdesivir and EIDD-2801 that gum up the virus's reproductive machinery when it enters a target cell. A second is to block the virus, like a bouncer outside a bar, from entering and infecting those cells in the first place. The third approach is to muffle the immune system's dangerously overactive response, a "cytokine storm" that can drown a victim in a mass of congestion and dying airway cells. To find these drugs, researchers have turned to the Food and Drug Administration's list of some 20,000 compounds approved for human use and crawled through drug patent applications looking for compounds with promising mechanisms of action. The goal has been to find drugs that have been at least partly developed, avoiding years of making therapeutic molecules from scratch. The Milken Institute, a health advocacy think tank, counted 133 experimental COVID-19 treatments in mid-April. About 49 of these therapies are being rushed into clinical trials. Their effectiveness in people is not yet known, and scientists caution that such drugs, like other anti-virals, are unlikely to be cures. But they could reduce symptoms enough to give patients' immune systems a chance to beat the virus on their own. COPY STOPPERSBecause all coronaviruses use the same molecular mechanism to reproduce, Baric says, that mechanism, which involves the enzyme nsp12, was an obvious target. Nsp12 normally corrects mistakes made by the main replication enzyme, RNA polymerase, as it as--sembles new virus particles. But remdesivir appears to work its way into nsp12's structure, disabling it. As a result, the virus's copying factory becomes sloppy and produces fewer new viruses. EIDD-2801, the compound with promising animal and test-tube results reported in early April, aims at the same viral enzyme. But unlike remdesivir, which much be given intravenously, EIDD-2801 can be taken as a pill. For this reason, Baric and other researchers investigating EIDD-2801, including George Painter, a professor of pharmacology and president of the Emory Institute for Drug Development, which first produced the drug, suspect it may end up being more widely used than remdesivir. In 2018 Painter and his colleagues identified EIDD-2801's activity during a search for a universal influenza medicine. When SARS-CoV-2 emerged, Painter's group immediately shifted focus. EIDD-2801, like remdesivir, inhibits the coronavirus's self-copying operations, but it also works against virus variants with a mutation that made them resistant to the Gilead drug. In addition, EIDD-2801 is effective against a host of other RNA viruses, so it could serve as a multipurpose antiviral, much as some antibiotics can work against a wide variety of bacteria. For COVID-19, says Wayne Holman, co-founder of Miami-based Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, which has licensed the drug and is planning clinical trials, the goal is to have a pill that can be taken by patients at home early in the course of the disease to prevent it from progressing. BLOCKING INFECTIONTo stop SARS-CoV-2 from penetrating cells in the first place, scientists are trying to develop antibodies that lock onto the viral protein that facilitates cell entry, a part of the virus known as the spike. Some of these neutralizing antibodies, made of a protein called immunoglobulin, may come from the blood of patients who have already cleared the virus. Several medical centers, including Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Mayo Clinic, are harvesting blood plasma from survivors and screening it for antibodies. In a technique known as convalescent therapy, doctors then transfuse it into hospitalized patients with life-threatening acute respiratory distress. Early studies of a few such patients suggest the approach may work—some patients' symptoms improved, and levels of the virus in their bodies dropped—but the work is very preliminary.  Takeda Pharmaceuticals, a Japanese firm, is also collecting plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients to identify antibodies. In that plasma, the company is identifying antibodies that show the most activity against SARS-CoV-2. Using these antibodies as a template, the Takeda researchers plan to synthesize a batch of even more active versions to create a potent cocktail of infection inhibitors, says Chris Morabito, head of research and development of plasma-derived therapies. The therapy—TAK-888—might enter clinical trials by year's end, Morabito says; the number "888" represents "triple fortune" in Chinese. Several other drugmakers, including Regeneron and Vir Biotechnology, are generating their own therapeutic antibodies and say they will also be tested in patients this year. Another blockade strategy focuses on the cellular docking site that the virus uses. Josef Penninger, a molecular biologist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and founder of drug company Apeiron Biologics, is trying to lure the virus away from a chemical receptor called ACE2 in the outer wall of lung cells. The coronavirus spike protein binds to this receptor. Several years ago Penninger's lab synthesized a decoy version of ACE2. In test-tube experiments, the scientists found the synthetic molecule—APN01—attracted coronaviruses away from real human airway cells. The virus locked onto the decoy and was marooned there. "We are blocking the door for the virus and, at the same time, protecting tissues," Penninger says. Apeiron is planning clinical trials later this year for APN01, which must be administered in the hospital as an infusion to sick patients. OVERREACTIONSIn the sickest COVID-19 patients, a mass of mucuslike fluid accumulates in the lungs, preventing cells from absorbing oxygen. These are the patients that need ventilators. The fluid buildup is the result of an overactive immune response that involves a signaling chemical called interleukin-6 (IL-6). Biotech companies, including Regeneron and Genentech, have manufactured synthetic antibodies that can bind to IL-6 and mute the call to action that it sends out. Northwell Health, a large system of 23 hospitals based in Long Island, N.Y., is one of more than a dozen centers participating in clinical trials of the IL-6 blockers, says Kevin Tracey, chief executive of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, which is running the trials at Northwell sites. "The hospitals are being inundated with very sick patients suffering from serious pneumonia and acute respiratory distress," Tracey says. "The IL-6 drugs have a plausible mechanism of action. I'm optimistic they'll work." None of these approaches are cures. Denison says the drugs under development may "reduce the severity" of an advanced COVID-19 episode, especially if they can be administered when initial symptoms—a mild cough, muscle aches or slight fever—first arise. In a hopeful future, a combination of various therapies may be able to thwart the virus on several different fronts, the way a cocktail of antivirals can beat back an HIV/AIDS infection. By limiting symptoms, drugs may be able to keep some patients out of the hospital and keep hospitalized patients off of ventilators. They can serve as a bridge to survival as other scientists rush to develop the real virus slayer: a vaccine. Read more about the coronavirus outbreak here. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "what can cause respiratory distress,what causes sars,what is acute respiratory infection" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Wow, cool post. I'd like to write like this too - taking time and real hard work to make a great article... but I put things off too much and never seem to get started. Thanks though. Rehab center Corona

ReplyDeleteriverside drug rehabilitation Thanks for a very interesting blog. What else may I get that kind of info written in such a perfect approach? I’ve a undertaking that I am simply now operating on, and I have been at the look out for such info.

ReplyDelete